As kitchens fill with warm scents of cinnamon, ginger and sugar for the holiday season, many people are unknowingly continuing traditions that stretch back centuries. According to Rebecca Sharpless, professor of history and chair of faculty senate, two of the most familiar holiday treats — fruitcake and gingerbread — are some of the oldest.

“Gingerbread is probably among the oldest,” Sharpless said. “Ginger was relatively cheap as a spice, and they could bring it from the Middle East, and it would make it to England. A lot of our baking heritage in the South is English.”

Sharpless notes recipes for gingerbread date back as early as the 15th century, and fruitcake, with its preserved fruits and alcohol, was specifically designed to last. She recalled the story of Eliza Middleton Fisher, whose wedding fruitcake was shipped from Charleston to Philadelphia in 1840 and arrived almost a year later.

“Eliza said after a 10-month delay, it was not quite as fresh as ever, but it is still in sufficient good preservation to be sent around,” Sharpless said. “So these people in Philadelphia got 11-month-old fruitcake.”

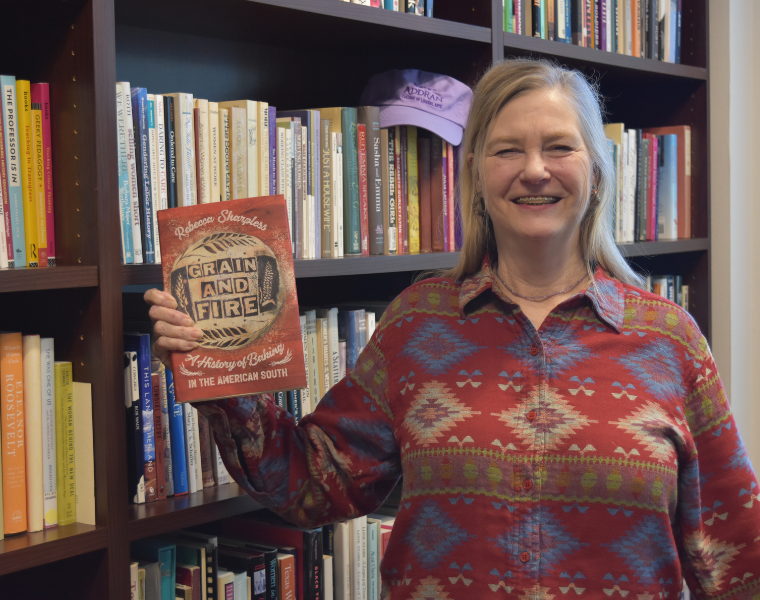

These kinds of moments — surprising, ordinary and deeply human — are at the heart of Sharpless’s research.

Research Rooted in North Texas

After moving to Fort Worth in 2010, Sharpless began noticing massive concrete grain silos rising over the Saginaw skyline. Curious about their purpose, she started researching their origin, a discovery that would eventually lead to her upcoming book, People of the Wheat, which explores how North Texans grew, milled, baked and ate wheat over time.

“North Texas was the center of wheat culture,” she said. “It was the furthest south of the main wheat-growing regions of the United States.”

Her discovery also challenged many common assumptions about what is considered “traditional” Southern baking. Much of what people associate with Southern desserts today, she notes, is actually quite modern.

“What we call Southern cake now, like coconut cake, is post-Civil War, because it depends on baking powder,” Sharpless explained. “If you see a recipe for ‘Old South’ coconut cake, it’s made up. It didn’t exist.”

Popular favorites, including red velvet cake and pecan pie, are also far younger than most people realize. Red velvet, Sharpless explained, was developed in the 1940s as part of a food coloring marketing campaign. Pecan pie didn’t become widespread until the Karo Syrup Company promoted it in the early 20th century.

“A lot of what we call Southern baking is just marketing,” she said.

Before industrialization, access to ingredients depended heavily on wealth and race.

“Wheat and sugar were a treat,” Sharpless said. “With enslaved people, they would eat corn the majority of the year, and they might get a little wheat flour for Christmas as a gift.”

For most families, enslaved and free, daily staples were molasses, cornmeal and pork. The light, fluffy cakes now linked to Southern hospitality were once reserved for the wealthy.

Even getting wheat into North Texas was a logistical challenge, she explained. Before the region began growing its own, flour had to travel by river and ox cart from as far away as St. Louis or New Orleans, often taking months to arrive, if it arrived fresh at all.

“By the time the flour got here, it might be moldy, might be nasty,” Sharpless said. “So, when people realized they could grow wheat here, they were just delighted.”

That realization transformed North Texas agriculture. Farmers could grow cotton and wheat side by side, creating a sustainable, profitable cycle that shaped both the landscape and the economy. It is this research that Sharpless discusses in her upcoming book.

A History Still Rising

As the holiday season continues and kitchens buzz with activity, Sharpless encourages people to consider what lies behind those familiar flavors.

Nearly every modern ingredient, like flour, sugar, spices and leavening, is the product of centuries of trade, labor and innovation. What now feels simple was once luxury. What now feels ordinary once required extraordinary effort.

“When you put flour in your hand, it feels soft,” she said. “And because it has gluten, when it’s leavened, it rises. Corn will never do that. That’s why people wanted wheat. And that’s why they were willing to work so hard for it.”

This year, as people bake with flour, they participate in a history rooted in soil, survival and ingenuity. Beneath every recipe is a story of migration, of labor, of culture and of love.

And in that sense, every kitchen becomes a small, fragrant archive, preserving the past one recipe at a time.