A new assistant professor of sociology, Edgar Campos, Ph.D.’s path to being a scholar of Latin America and a teacher was not the most direct one. The son of Mexican parents and growing up in California, Campos did not believe he would attend college, let alone become a professor.

“My family was poor and growing up there was only one person on either side of my family who had ever attended college,” he said.

Now, Campos comes to Fort Worth ready to bring his skills as a scholar and research, and his life experience, to the TCU Community and speak about unique societies of Latin America and their impact around the world.

Humble, Heroic Family History

Campos’ family is from the Mexican state of Michoacán, in the country’s southwest, bordering the Pacific Ocean.

“My mother first came to the U.S. at the age of 6 when her father was contracted to work in the fields of California before moving back at the age of 12,” Campos said. “My father first came when he was 18 years old to work the fields in California.”

The family was poor, and Campos worked manual labor jobs from an early age, something he decided was not for him.

“I worked in the family catering business and other manual labor jobs,” he said. “I did not want to do manual labor for the rest of my life, especially seeing the detrimental physical toll on my male relatives.”

Campos enjoyed sociology and history at school but was never taught about Mexican or Latin American culture or history unless, he said, the subject matter were things like drug cartels, violence and dictatorships.”

The experience, Campos said, shaped his focus as an academic into learning why “the political nature of culture and history to understand why my people, region and culture was pushed aside or talked about only in the negative.”

He would go on to college and earn his bachelor’s degree from California State University, Sacramento.

In a further sign of connection to Mexico, Campos is a distant relative of one of the most revered figures in Mexican history, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. A Catholic priest-turned-revolutionary leader, the Mexican Government refers to Hidalgo y Costilla as “Padre de la Patria” (Father of the Nation). He is one of the central figures in Mexico’s eventual independence from Spain. A relative discovered the connection.

“He found our family’s connection to Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla through family documents and letters,” Campos said.

Further exploration of family history would unearth family connections to the Mexican Revolution and the Cristero War.

Campos is a dual national, holding U.S. and Mexican citizenship, and said he uses that experience and identity in the classroom.

“I use my dual nationalities to discuss examples within the American context to help students understand through their lived experiences, cultural understanding, and everyday realities and then compare it to Mexico and Latin America,” he said. “One of sociology’s main principles on society is that it is a social construction. One example that students enjoy is contrasting the American concept of individualism to that of Mexico/Latin America familial system that dictates family dynamics, social roles and connection to their broader community.”

Mexico City 1968

The Olympics are important shared cultural events by nations around the world, but Campos argued in his doctoral thesis that the 1968 Summer Olympic Games, held in Mexico City, were especially influential.

The Games that year featured innovations associated with the Olympics today and wider society. They include the Cultural Olympiad exchange between nations, government support for The Games, color broadcasting and iconography to represent the different events and aid tourists’ navigation of Mexico City. According to Campos, the icons for The Games, created by Mexican architects Pedro Ramirez Vazquez and Eduardo Terrazas, and American Lance Wyman, were so successful that the resulting use of iconography led to how modern users navigate their mobile phones.

The 1968 Mexico City games also set the tone for diversity and gender equality for future Olympics.

“For the first time, a developing nation was hosting the Olympics. Post-colonial nations from Africa, Asia, and Latin America also had a voice,” following decolonization, said Campos.

The Games featured the first woman to light the Olympic cauldron and the first to display indigenous peoples, something that would not be repeated until the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia.

Yet, according to Campos, the 1968 Mexico City Olympics are remembered in popular culture for controversial moments, like the Black Power salute of Tommie Smith and John Carlos and the tragedy of the Tlatelolco massacre, where students protesting the coming Olympics were killed by members of the Mexican armed forces.

“The legacy of the event is unfortunately that history never gave proper credit to Mexico for its unique contributions to the modern Olympic Games,” Campos said. “Understanding the event itself and its memory helps understand international relations.”

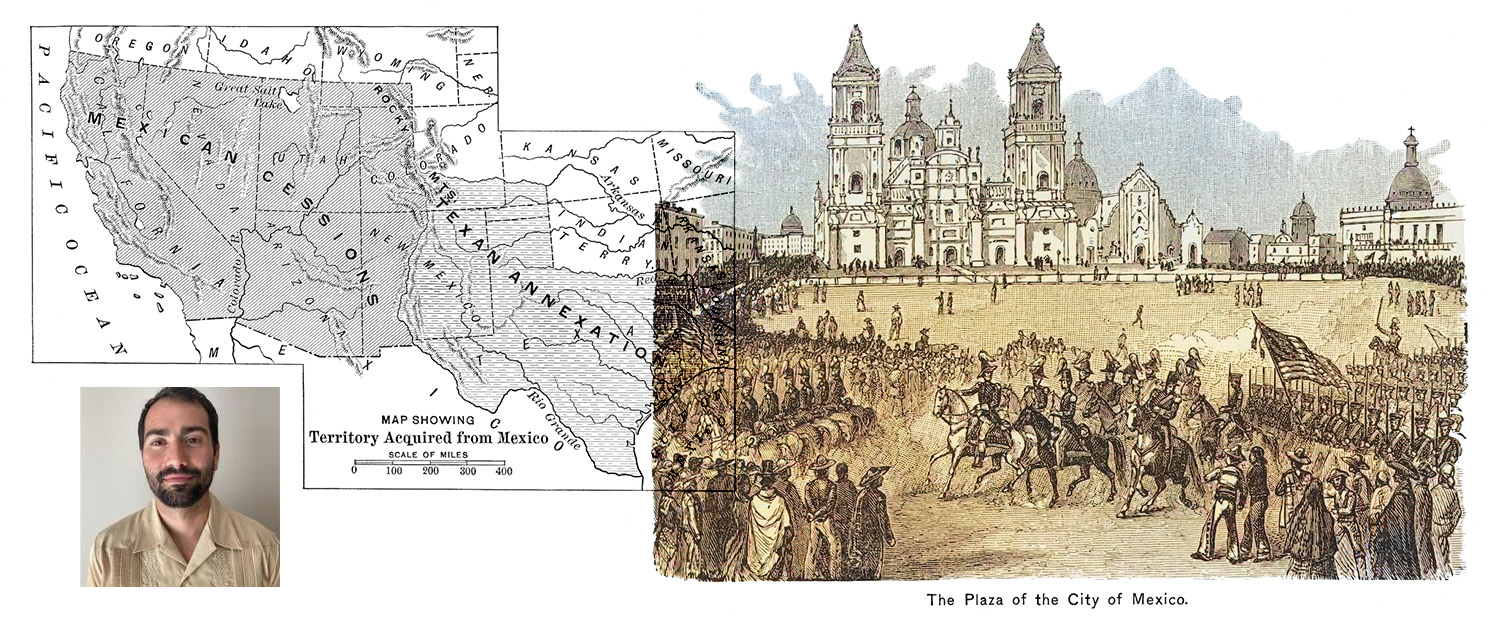

Understanding the Mexican-American War

As he settles into his role at TCU, Campos says his research focus now centers on the Mexican-American War and how museums on both sides remember and teach the conflict.

“The goal of my research into the Mexican-American War is to show the power of history. Here you have a conflict that is understood completely differently on either side of the border,” said Campos. “History is very much written from the perspective of the winner, but there is a lot to learn from the perspective of the loser. It is important to understand the cultural and political ramifications of history.”