Hanan Hammad, Ph.D., on the Extraordinary Egyptian Movie Star and Singer

Here is the story: a female singer becomes a movie star, has a tumultuous personal life, finds herself engulfed in scandal and political intrigue but through it all, becomes a cultural icon, relevant through the present day.

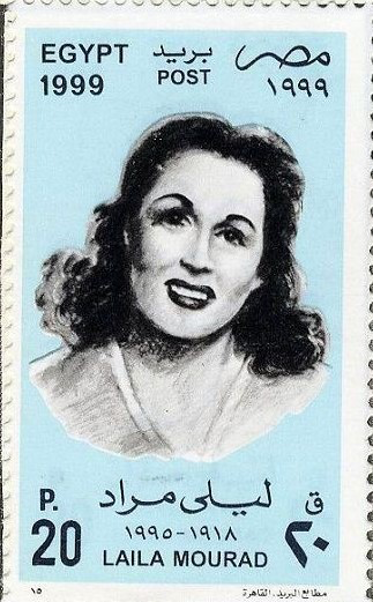

While this might sound like the plot of a 2023 Academy Award nominee, it is actually a rough outline of the life of Layla Murad, an Egyptian singer and actor of Jewish heritage who converted to Islam, and the subject of Hanan Hammad, Ph.D.’s latest book, Unknown Past: Layla Murad, the Jewish-Muslim Star of Egypt (Stanford University Press, 2022).

Hammad is no stranger to telling the stories of women in the Middle East, having written Industrial Sexuality: Gender, Urbanization, and Social Transformation in Egypt (University of Texas-Austin Press, 2016). The book was recognized five times, including book award wins from the National Women's Studies Association and Association of Middle East Women’s Studies.

With her book receiving praise from outlets such as Arab News and Al-Fanar Media, a news site focused on Arab culture, Hammad sat down to talk about Layla Murad’s incredible life.

Challenging Beginnings

Layla Murad was born into a family of Egyptian Jews in 1918. Her father, Zaki Murad, was a well-known singer and active in Egyptian nationalist politics. Murad grew up in a “middle class, urban” home in Cairo, but her father’s financial recklessness would hurt the family, according to Hammad.

During a tour of Arab diaspora communities in North and South America in the late 1920s, Zaki used his earnings to buy stock. The Great Depression began, plunging the Murad family into poverty. Zaki, gone for four years, returned to Egypt “penniless,” forcing the young Layla to quit school and learn a trade to provide for her family, Hammad said.

Zaki discovered his daughter’s talent and began to nurture her career, eventually becoming her manager. Murad’s music was “a product of her time,” said Hammad. The music was “fluid between different genres to impress different audiences,” according to Hammad, with songs on love and Arab classics in her repertoire.

Murad’s name became well-known in the Arab world thanks to two inventions: the microphone and radio. Microphones amplified her naturally soft voice and the Egyptian government’s creation of a national radio network in 1934 brought Murad’s music to the masses.

“Her voice and image, she becomes a national icon. Everyone recognized her,” Hammad said.

Layla at the Movies

Murad’s career eventually transitioned from music to the movies. In the 1930s, 40s and 50s, Egypt was “the Hollywood of the Middle East,” Hammad said.

Murad’s career got off to a difficult start, with her early work with a director who Hammad described as “toxic masculinity” in practice. Despite the difficulties, the film was a hit. Several films with director Togo Mizrahi would raise Murad’s credibility as a star and leading woman.

However, it was her relationship with Anwar Wagdi, according to Hammad, that would have the biggest impact on Murad’s life. The two worked together as co-stars and eventually married. Wagdi produced several films co-starring with his wife, something that brought him power in the movie industry.

Away from the movie success, Murad and Wagdi had a troubled home life. “Every couple has personality clashes, but when you do this under the light of fame, everyone sees what you are doing,” said Hammad. The couple separately invited the tabloid press into their lives, as a way to “always want to feed the curiosity and interest the audience, so they come to watch you and buy tickets,” according to Hammad.

A Question of Faith

Hammad said that the subject of Murad’s Jewish faith and family heritage was not an issue during her singing career or when she was acting in the 1940s. “No, it was not a big deal at all. Entertainers from minority communities were almost the norm (at the time),” said Hammad. That would change.

In 1952, rumors in Syria began circulating that Murad had visited and given money to Israel, causing a scandal. Arab states such as Syria refused to recognize or establish normal relations with Israel since its founding in 1948 following the first Arab-Israeli War and the displacement of Palestinians living in the area.

The accusations were not true. For her book, Hammad discovered Murad publicly released “all her bank statements, she showed her visa and passport, which showed she was in France with her husband at the time she supposedly visited Israel.”

The new regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser, called the Free Officers Movement, had embraced Murad as a symbol, conducted an investigation and cleared her. Hammad was satisfied the government investigation was conducted properly and said she was “amazed at the recklessness of the accusations.”

Hammad said the insinuation that Murad was sympathetic to Israel because of her Jewish heritage was inaccurate because she quietly converted to Islam sometime in 1946 and registered her new religion in government records in 1947. In 1948, Murad said the choice to convert was a “private” one made shortly after her marriage to Anwar Wagdi and she did not widely announce it out of respect for her father’s feelings.

However, Hammad’s research left her convinced that although Murad’s conversion to Islam was personal, the publicity around it in 1948 was motivated by more than personal choice.

One reason was events happening in the region at the time. “I don’t doubt her intention, but having publicity around it in the summer of 1948 is definitely because of the war in Palestine (between Arab states and Israel),” Hammad said.

Furthermore, Hammad said Wagdi was concerned about his wife working with other producers and directors outside his control. Murad said she worked with other collaborators out of a need to provide for her extended family. That tension was exacerbated by the unequal terms of the marriage between the Jewish Murad and the Muslim Wagdi.

“Marriage is a contract in Islam. You can put any conditions you want in a marriage contract,” Hammad explained. The Egyptian state, charged with upholding Muslim marriage contracts, treated interfaith couples differently. “My biggest surprise is that the contract, the form (between Wagdi and Murad) is not the standard form for any marriage contract at the time, but for an interfaith marriage,” she continued.

Because of her Jewish heritage, Murad’s marriage contract with Wagdi “put the minority wife (Murad) in a weaker position.”

Murad was a powerful force in Egyptian media at the time, and the marriage to Wagdi led to a kind of “surrendering of her agency” said Hammad.

Legacy

The accusations of travel to and financial support for Israel had little impact on Murad. However, her secret marriage to one of Nasser’s comrades, Wagih Abaza, stopped her acting career in 1955. Murad had her first son with Abaza.

Following the short-lived marriage, Murad married for the third time. Although she wished to return to cinema, she never appeared in another film and passed away in 1995. Murad is still one of the most beloved stars among Arab audiences.

“Because of her persona, people would relate to her as if she were their daughter." - Hanan Hammad, Ph.D. on Layla Murad's appeal to audiences

Of all her films, Hammad recommended those interested to watch 1949’s Ghazal al-banat (The Flirtation of Girls). The film is widely considered a classic and Hammad said she uses it to counter stereotypes of the Arab world in her classes.

Hammad said what made Murad great was her relatability. “Because of her persona, people would relate to her as if she were their daughter,” Hammad said.