Reposted from TCU Magazine

Recreating Iron Gall Ink

To test the iron gall ink recipe that he mined, (History Professor) Hidalgo recruited Kayla Green, associate professor of chemistry.

“IT WAS EXCITING TO ENVISION THE USE OF CHEMISTRY TO HELP TEACH SUCH A HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT LESSON.”

KAYLA GREEN, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF CHEMISTRY

“It was exciting to envision the use of chemistry to help teach such a historically significant lesson,” Green said. “As anyone who has taken one of my chemistry courses will tell you, I have a personal interest in history and the individual stories of the characters involved.”

Under Green’s guidance and with the aid of modern glassware, stirring rods and liquid reagents, Hidalgo and his students attempted to re-create iron gall ink — the same kind used to pen the Declaration of Independence. Green concocted a batch ahead of time, and it looked authentic. Still, Sarah Miller ’19 MA said she harbored some doubt.

“I didn’t think it was going to work,” said Miller, who had confidence in her skills as a historian but was in less familiar territory in the chemistry lab.

In fact, Miller and her classmates were unable to replicate the viscosity typical of iron gall inks in the 16th to 18th centuries. Instead, they produced something thinner, more like watercolor.

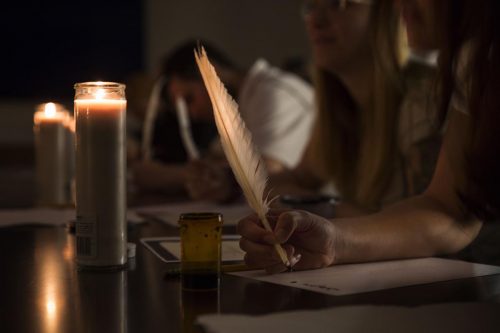

Scriptorium by Candlelight

Since that first iron gall ink experiment, Hidalgo has added a component to the syllabus called the scriptorium by candlelight, which simulates the 17th- and 18th-century writing process. He learned of this exercise through the Andrew W. Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography, a fellowship he received in 2019 that aims to advance the study of rare books as material objects.

During an exercise called scriptorium by candlelight, Alex Hidalgo’s students copy Spanish manuscripts using handmade iron gall ink and quills. Courtesy of Alex Hidalgo | Photo by Scott Murdock

“I turn out the lights, and I have my students copy by candlelight samples of colonial Spanish manuscripts using rag paper — the type used in the early modern era — and the iron gall ink and the handmade quills they made during the lab.”

Hidalgo said the hands-on nature of the ink experiment and follow-up scriptorium underscore how knowledge of craft works.

“It takes practice and experimentation, and it’s passed down through generations,” he said. “Also, [the experiment] illustrated how new knowledge and understanding comes by transdisciplinary research — combining efforts across disciplines.”

Hidalgo is designing an undergraduate course that will incorporate astronomy into the study of Latin American history. The class will include a trip or two to an observatory, he said.

“In our readings, we look at how people used the stars for various purposes like mapping, determining weather patterns and even explaining human behavior,” Hidalgo said. “I’m hoping that by collaborating with an astronomer, we can learn about how the different alignments of stars have been understood across time and how modern-day astronomers understand it all within their discipline. I’m really just trying to make Latin American history come alive.”