A Panel of Native American Leaders Discuss How Government, Christian Denominations Used Boarding Schools to “Assimilate” Native Americans and Steps Forward.

“TCU acknowledges the many benefits, responsibilities, and relationships of being in this place, which we share with all living beings. We respectfully acknowledge all Native American peoples who have lived on this land since time immemorial. TCU especially acknowledges and pays respect to the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, upon whose historical homeland our university is located.” – TCU Native American Land Acknowledgment

A group of Native American leaders visited the Brown-Lupton University Union to discuss the implications of a recent string of discoveries of mass graves of Indigenous children on the sites of former Canadian residential schools, and the subsequent U.S. government response around our country’s American Indian boarding schools.

“A Frank Discussion about American Indian Boarding Schools, Christianity, and Their Legacies” heard three Native American leaders and audience members discuss the traumatic legacy of the boarding school system, the role Christianity played and the path toward healing.

What Were the Boarding Schools?

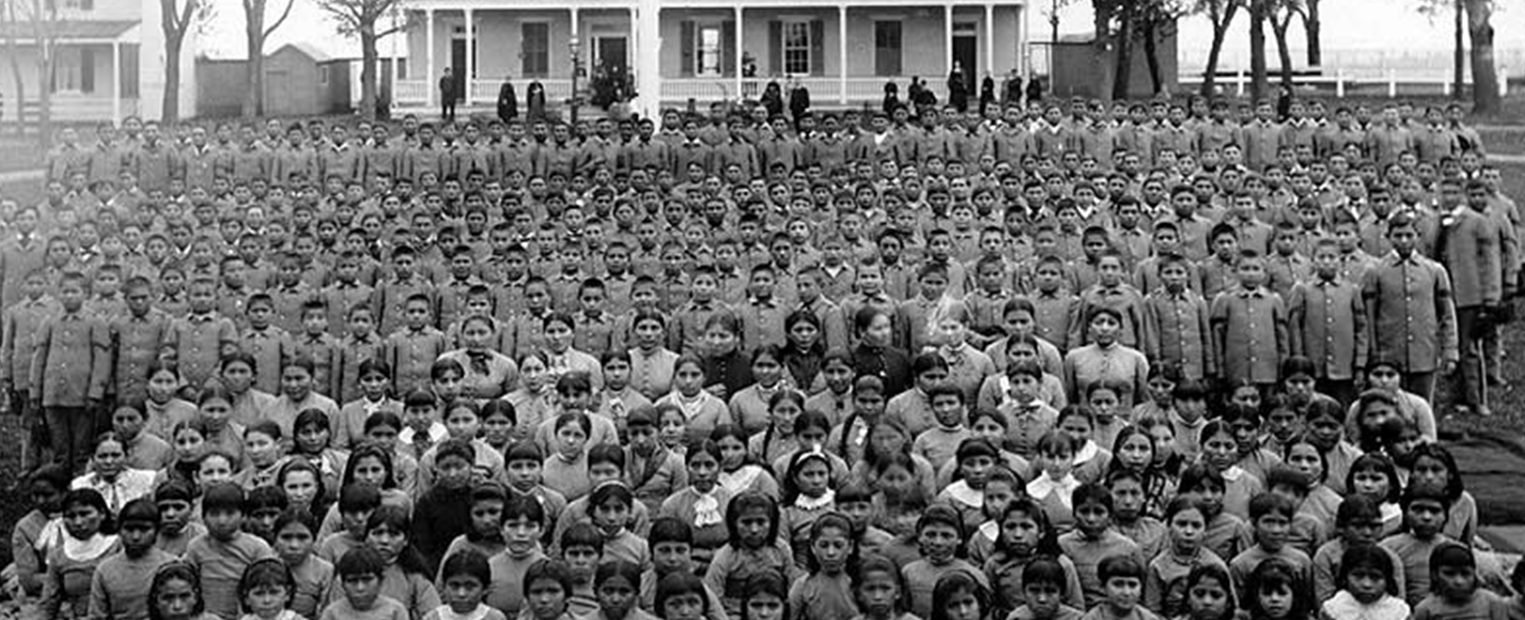

As part of the ongoing efforts by Europeans and Americans to colonize and push out the Indigenous inhabitants of what would become the U.S., Christian denominations and the U.S. government created boarding schools that removed Native American children from their parents and communities. The idea was to “civilize” the children by removing all traces of their culture, forcing the adoption of English, western dress and other methods. The boarding schools were often the sites of exploitation, horrific physical and emotional abuse, and tragically, death.

The federal government sanctioned, encouraged and funded boarding schools from the early 1800s up till the 1960s. Oftentimes boarding schools would be entrusted by the government to Christian denominations. Survivors of boarding schools and their tactics are still living in 2021.

With the recent discoveries in Canada, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland directed her department to create the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, an investigation into the government’s policies around and support for boarding schools.

“I know that this process will be long and difficult. I know that this process will be painful. It won’t undo the heartbreak and loss we feel. But only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that we’re all proud to embrace,” Haaland said in a statement.

Boarding Schools Gone, but Impact Still Felt

The discussion of the legacy of the boarding schools and the implications for Christianity was led by a stellar list of local North Texas and Oklahoma Native American leaders. They were:

- Jodi Voice Yellowfish (Muscogee/Creek, Oglala Lakota, and Cherokee) is a Dallas-based activist and member of the City of Dallas’ Arts & Culture Advisory Commission. She is considered one of the first Native Americans appointed to a city board or commission.

- Annette Anderson (Chickasaw and Cherokee) is a licensed clinical social worker and a member of the Plano-based Council for the Indigenous Institute of the Americas (IIA). Anderson is a member of the TCU Native American Advisory Circle and frequent speaker on campus.

- Chebon Kernell (Seminole Nation of Oklahoma) is Executive Director of the Native American Comprehensive Plan for the United Methodist Church. Since 2015, Kernell has been deeply involved in advancing the relationship between TCU and the Native American community. He is a frequent campus speaker and a member of the Native American Advisory Circle.

The panelists were introduced by Scott Langston, Ph.D., instructor of religion and TCU’s Native American Nations and Communities Liaison.

Reflecting on the legacy of boarding schools, Kernell said the fact that it took the discoveries in Canada and subsequent reactions to have conversations about boarding schools and Christianity should be instructive. “This is our history. This is what happened to us. And we have celebrated this moment, that we survived, because of that history,” he said.

The panelists said the boarding schools and the faith that often operated them promoted white supremacy and an institutional racism that persists to the present. They also agreed that the system caused deep trauma within generations of Native American communities, something that Native Americans must come to terms with. Anderson said the legacy of the boarding schools had separated Indigenous peoples from their culture, something present-day Native Americans needed to reclaim.

Kernell said that Christianity had not fully come to terms with its involvement in the boarding schools. All the panelists agreed that reflection and recognition of the injustices of the boarding school systems was needed, both by practitioners of Christianity and wider American society.

Going forward, Yellowfish asked audience members to listen to Native American people on issues relevant to them, and recognize that their experience makes them "experts without a Ph.D." The TCU community had a responsibility to learn more and continue to build on its relationship with the Native American community.

Final Thoughts

Reflecting on the event, Anderson commended TCU for taking on a topic often ignored in wider culture. “As caring people, it is painful to think about and talk about the young human beings who died at the hands of strangers in the name of Christianity,” she continued.

“As a panelist, I realize it is just the beginning. We must be open to hearing the truth from the survivors and understand the lifelong intergenerational damage that has been done to the American Indian community,” she concluded.

“We learned tonight that there are many facets and deep pain and trauma to boarding school experiences, which continue today,” Langston said.

He said that the issue of boarding schools was “just one manifestation of the historical and ongoing colonization that seeks to take Native American lands and eradicate them physically, culturally, and in other ways.”

“To overcome this at TCU and in our nation, we must admit that colonization is just as serious an issue as any other of the issues we are attempting to address as part of our diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts,” Langston continued.

“Reconciliation must include the university's relationship to colonization and Christianity. Acknowledging this connection is the first step,” he concluded.

Resources

TCU Native American & Indigenous Peoples Initiative

TCU Native Land Acknowledgment

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition